Words Before Blades: Fechtersprüche and Fechtreime in 16th Century German Fechtschulen

In the urban centres of 16th century southern Germany, fencing was conceived not merely as a physical skill but as a public performance of honour, discipline, and civic identity. Public fencing contests, known as Fechtschulen, were regulated events staged before spectators and governed by social expectations that extended well beyond technical proficiency. Within this performative environment, short spoken verses—referred to as Fechtersprüche (“fencers’ sayings”) or Fechtreime (“fencing rhymes”)—appear to have played a meaningful role. Recited prior to combat, these verses articulated confidence, piety, and commitment to the fencing art, reinforcing the notion that fencing belonged within a moral and cultural framework rather than the realm of uncontrolled violence.

Fechtschulen as Civic Performance

A contemporary description of Fechtschulen as public and civic events is provided by the Strasbourg fencing master Joachim Meyer. In his Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (1570), Meyer explains that it was customary in free imperial cities and other towns to hold public fencing schools at which practitioners could test themselves against one another, “not in murderous earnest”, but so that “honour, manhood, and skill may be seen”.¹ Meyer repeatedly emphasises discipline, order, and restraint, warning against hatred and reckless anger so that all participants might depart with their honour intact. He further insists that fencing at such events must be intelligible to spectators, as skill that is poorly displayed fails in its social purpose.

Meyer’s account makes clear that Fechtschulen were not private exercises or chaotic brawls but regulated civic spectacles in which behaviour and self-presentation were subject to communal judgement. This environment was well suited to ritualised speech, in which combatants framed their participation verbally before engaging physically.

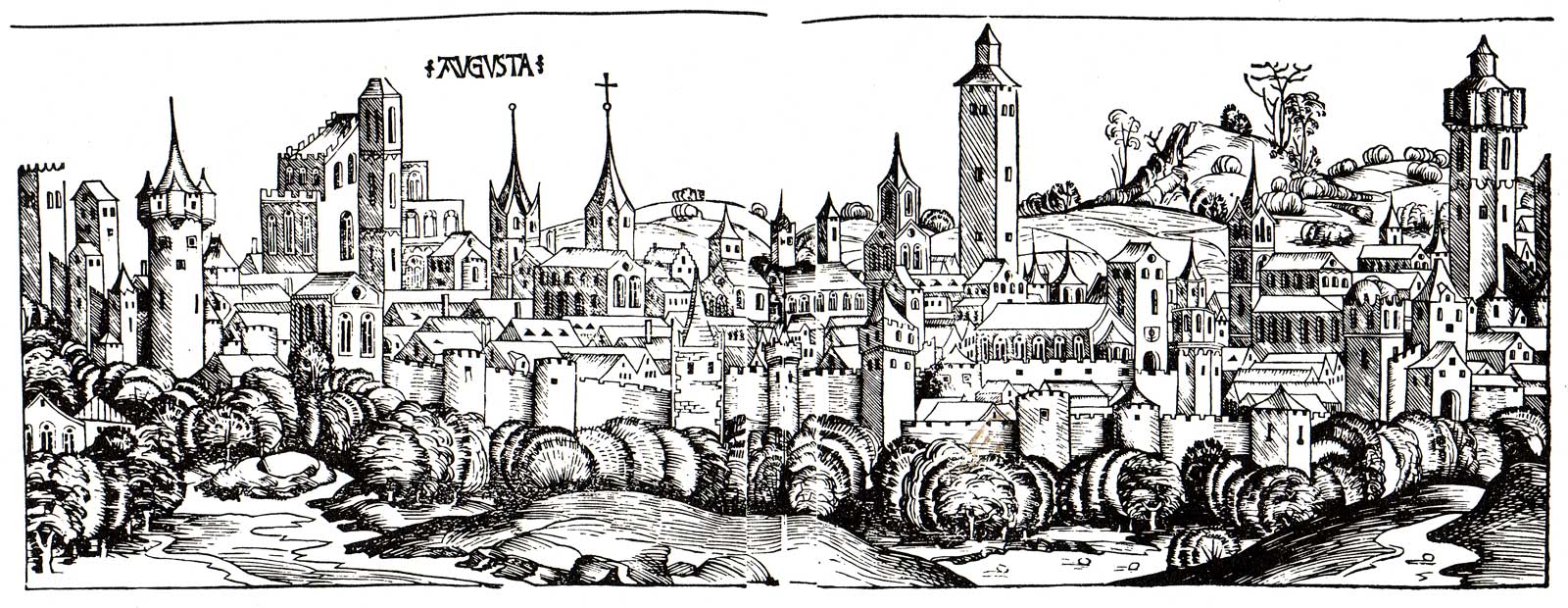

Simprecht Kröll and the Augsburg Fechtschulen

An important non-professional perspective on these events is provided by the Augsburg weaver and chronicler Simprecht Kröll, who recorded local occurrences in Augsburg during the years 1551–1552. Among these notes are references to Fechtschulen held in the city. Although Kröll’s chronicle survives only in manuscript and has not been published in a complete modern translation, secondary scholarship reports that he noted the recitation of short rhymed sayings by combatants before fencing.² These verses are described in modern literature as Fechtersprüche or Fechtreime, terms which emphasise both their performative function and their poetic form.

Kröll’s interest in these spoken elements suggests that they were sufficiently conspicuous to be regarded as an integral part of the event. Their recitation marked a transition from ordinary social interaction to regulated combat, allowing the fencer to present himself as articulate, literate, and self-controlled. In an urban society where literacy and verbal skill were important markers of status, such speech reinforced the understanding of fencing as an honourable civic art rather than mere physical aggression.

Fechtersprüche and Fechtreime: Form and Function

Although the precise wording of the verses noted by Kröll has not survived in translation, their likely form and rhetorical function can be inferred from contemporary fencing poetry and guild verse. These sources demonstrate how rhyme and first-person declaration were employed to articulate martial identity in a controlled and socially intelligible manner.

A particularly instructive example is the longsword poem composed in 1538 by Hans Czynner, preserved in a fencing manuscript and available in modern English translation. Written in the first person, the poem combines technical assurance with assertions of honour:

“Whoever I fight with courage,

whoever takes the sword in hand,

I subject him to my honour.

He may cut finely,

but I hinder him,

and strike in from the bind.”³

The poem’s confident tone, technical references, and emphasis on honour align closely with what might be expected of a Fechterspruch. It asserts mastery and control without invoking uncontrolled rage, presenting fencing as a rational and disciplined art.

Comparable language appears in verses associated with the Federfechter, one of the principal fencing guilds of the sixteenth century. Surviving rhymes, known through later citations and translations, include assertive declarations such as:

“Who scorns me and my praiseworthy art,

I shall strike upon the head

until it rings within his heart.”⁴

Here, physical violence is openly acknowledged but framed as a defence of the fencing art itself. The speaker’s identity is tied not merely to personal strength, but to membership in a recognised and honourable tradition.

Further short moralising verses embedded in fencing manuals reinforce the same themes:

“Trust in God and in your art;

fence with measure, not with rage.

Thus you gain honour,

and lose no man’s goodwill.”⁵

Such lines combine piety, restraint, and professional pride—values that resonate strongly with Meyer’s prescriptions for conduct at Fechtschulen and with the civic ethos implied by Kröll’s observations.

Speech, Literacy, and Martial Identity

Taken together, these sources suggest that Fechtersprüche and Fechtreime were more than decorative flourishes. In the performative space of the Fechtschule, spoken verse helped to frame combat as disciplined, honourable, and socially meaningful. Recitation demonstrated literacy and composure; invocation of God or the fencing art underscored ethical restraint; and public declaration transformed physical confrontation into a sanctioned civic contest.

Kröll’s brief Augsburg notes gain greater significance when read alongside fencing manuals and poetic sources. While Meyer articulates the ideals governing Fechtschulen, and Czynner and guild poets preserve the language of martial self-assertion, Kröll provides rare evidence that such practices were noticed and recorded by contemporary urban observers.

Conclusion

Fechtersprüche and Fechtreime occupied a liminal space between speech and violence, intellect and physicality. In sixteenth-century German Fechtschulen, words preceded blades, framing combat as a disciplined and honourable practice embedded within civic life. Although the precise verses recorded by Simprecht Kröll remain unpublished in translation, surviving fencing poetry and guild rhymes allow us to reconstruct their likely tone and function. Together, these sources reveal a martial culture in which the spoken word was an essential counterpart to the sword.

Footnotes

- Joachim Meyer, Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Strasbourg, 1570), translated excerpts in Wiktenauer, sections on Fechtschulen and public fencing practice.

- B. Ann Tlusty, “Martial Identity and the Culture of the Sword in Early Modern Germany”, in Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books, ed. Daniel Jaquet, Karin Verelst and Timothy Dawson (Leiden: Brill, 2016), discussion of Augsburg Fechtschulen and Simprecht Kröll’s chronicle notes from 1551–1552.

- Hans Czynner, “Poem about Longsword Fencing” (1538), English translation via Wiktenauer; see also Keith Farrell, translation and commentary.

- Federfechter guild verse, translated excerpts cited in secondary literature on sixteenth-century fencing guilds; see Tlusty, “Martial Identity”, and related discussions.

- Anonymous moralising verse from sixteenth-century fencing manuals, translated excerpts as preserved in modern scholarship.

Bibliography

Czynner, Hans. Poem about Longsword Fencing. 1538. English translation via Wiktenauer and Keith Farrell.

Meyer, Joachim. Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens. Strasbourg, 1570. English translations via Wiktenauer.

Tlusty, B. Ann. “Martial Identity and the Culture of the Sword in Early Modern Germany.” In Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books, edited by Daniel Jaquet, Karin Verelst and Timothy Dawson, 179–204. Leiden: Brill, 2016.

Wiktenauer. “Historical European Martial Arts Wiki.” https://wiktenauer.com

< BACK